Strings Magazine

By James Reel

April 2007

Excerpted from Strings magazine, April 2007, No.148

Heart Full of Soul

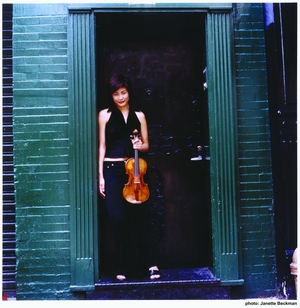

Violinist Jennifer Koh has reached beyond the confines of the typical virtuoso.

Photo Credit: Janette Beckman

You’ve got to love Jennifer Koh for more than just her brain. Oh, sure, at age 17, when she won the top violin prize in the International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow, she nixed the idea of becoming an instant touring virtuoso and high-tailed it back to Oberlin College to finish her degree—in English literature. And, yes, she had the idea of recording a disc of Szymanowski, Martinü, and Bartók concertos after reading the complete works of Czech novelist and essayist Milan Kundera.

Yet Koh is most certainly not the sort of person to intellectualize all the emotion out of music. Says her mentor, violinist Jaime Laredo, “She’s very outgoing, almost flamboyant, but in a very good way, not in an ostentatious way. And she really touches the heart, because she plays from the heart.”

Koh was born in the Chicago area and pretty much started her career at the top; by age 11 she had already soloed with the Chicago Symphony. In the 1994–95 season alone, she won the International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow, the Concert Artists Guild Competition, and the Avery Fisher Career Grant. She got that English-lit degree from Oberlin, along with a performance diploma from Oberlin Conservatory, then for “finishing school” she chose the Curtis Institute of Music, from which she graduated in 2002 as a disciple of Laredo and Felix Galimir.

For the past few years she’s been out on her own, proving that the former child prodigy has become a remarkable adult musician, both thoughtful and vibrant. As a laureate of the Tchaikovsky competition, she’s asked to play the Tchaikovsky concerto a lot, as well as the usual Sibelius and Bruch chestnuts. But her orchestral appearances this season also involve Leonard Bernstein’s Serenade, Kaija Saariaho’s Graal Theatre, György Ligeti’s Violin Concerto with a cadenza she commissioned from John Zorn, and the premiere of a concerto by Charles Wuorinen. Her duo recitals with pianist Reiko Uchida are an unexpected mélange of Schubert, Schumann, Poulenc, Kurtág, and a brand-new sonata by Jennifer Higdon.

Higdon, one of today’s most prominent American composers, teaches at Curtis, and that’s where she first noticed Koh. “I was always impressed by her excitement over new music and her constant curiosity about what's being written now,” says Higdon.

“Jennifer is an impeccable musician, with incredible energy in her playing, and a real sensitivity to whatever style she is playing in. I love her open sense of handling everything from an atonal work, to the most lush romantic piece, to a jazz-based piece; there’s real skill there and the pieces all sound like they fit perfectly in the world in which they’ve been written.

“She is dedicated to giving her all in both old works and new.”

Perhaps Koh’s flair for so many different kinds of music is related to her own intellectual eclecticism. As a child and college student, she didn’t just lock herself in a closet and do music, music, music. She says getting a degree in literature is one of the best things she ever did as a developing violinist.

“Musicians find their points of inspiration in different places. For me one of those points of inspiration comes from literature and poetry,” she says. “It is very relevant to me still, in a lot of the ways I program recitals and CDs. The Portraits CD (with the Szymanowski, Martinü, and Bartók) was inspired by going through a huge phase of reading all of Milan Kundera’s translated works in English. He writes so beautifully about music; very often music is a metaphor for life in his writing, which is also true in my own life. He speaks a lot about Janác?ek and other composers from that region of Bohemia, and it became the starting point for thinking about this CD.”

This kind of thinking is nothing new for Koh.

Says Laredo, “Teaching Jennifer was a pure joy. She was so curious; she wanted to learn so much. She couldn’t get enough. She was hungry all the time. She wasn’t interested in just playing the fiddle. Her interests ran the gamut from Bach to John Adams. She was a fast learner, and now she has this incredible career.

“I’m so proud of her I can’t tell you.”

Before signing up with Laredo at Curtis, Koh pursued the literature degree, she says, because “it was important to expand my range of knowledge. One of the things I’ve always believed is that your art form is a reflection of who you are and your interests. I was very drawn to literature and especially poetry from the very beginning. Poetry is very close to music in the sense of how a writer decides to choose a comma or a semicolon or a break in the line. Everything in poetry means something more, in the sense that each word represents something more, metaphorically, than what it literally is.

“In a piece of music, each note by itself has very little meaning, but if you listen to an A major chord, it’s all about the relation between the notes. And as a musical line develops, it’s the relations between the notes and the time between the notes, the commas and semicolons, that give them meaning. That’s what I love so much about being a musician: You’re part of something so much greater than yourself, and the experience is so much greater than yourself alone.”

She’s not just talking about playing a concerto in front of a 100-piece orchestra. She’s also talking about chamber music. Koh spent the summer of 2005 playing chamber music at Marlboro, and then that fall she formed the Variation String Trio with violist Hsin-Yun Huang and cellist Wilhelmina Smith.

She’s also talking about working with composers living and dead, getting into their heads and hearts through their scores, and developing personal relationships with those who are still alive, notably Higdon and Zorn.

“Jennifer is an unusual case,” says Higdon, “because you can craft absolutely anything and she’ll play it; that’s the kind of thing that composers just dream about. [She] has a range of repertoire that runs the entire gamut of what’s out there, from the simple and elegant to a gnarly complexity that would make your hair stand on end! She does it all and does it very convincingly. So when I was writing String Poetic for her, my main thought was to give her a piece with a series of movements that could be stand-alone works, and to vary the movements in temperament and even musical language. Her playing adjusts beautifully with each character change in the music.

“She’s very smart, and a hard worker. She has a good combination of raw talent and finesse in her playing. When she's playing in a concert, you feel like you're right there experiencing the music with her. There's no sense of a separation between the audience and the performer. It’s truly a shared experience.”

Koh has been praised for her tone, technique, and intonation even when she’s playing thorny new music. A few decades ago, new music often wasn’t played very well. But Koh, like many other new-music advocates today, believes that one must apply the same standards to performance of contemporary music as to Beethoven. “It takes the same amount of concentration and interest,” she asserts. “One of my teachers was Felix Galimir, and he worked closely with Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg, and even Ravel. And Szigeti had a close relationship to Bartók. One of the greatest creative processes to be a part of is to work with composers. You have the composer right there to ask any questions you have. Sometimes there are questions about what these markings mean, but what I find so fascinating about it also is that I have a chance to ask them what their inspiration point was for a particular work.

“It’s so fulfilling.”

Koh doesn’t drop names like Galimir and Szigeti lightly; she’s an avid collector of historical recordings. “It’s a personal obsession,” she admits. One of her favorite violinists of the recent past is the Belgian Arthur Grumiaux. “There’s an incredible elegance and incredible purity to his playing that I very much connect to, and an integrity also.”

Koh is proud to play an instrument once owned by Grumiaux (see sidebar, “What Jennifer Koh Plays”).

As impassioned as her own playing can be, her admiration of the suave, patrician Grumiaux shows that she’s not interested in developing a reputation as a firebrand. In fact, she shuns the label virtuoso.

“Being a good musician is, in a lot of ways, more about your ability

to listen than using your ability to play,” Koh says. “Being

a virtuoso is not the most important aspect of music. I’d just like

to think of myself most as a good listener, and as a musician."

Photo Credit: Janette Beckman

Music Messenger

Jennifer Koh’s outreach project, Music Messenger, takes her into schools to give concert-demonstrations and interact with middle- and high-school kids in America, Japan, and Germany, especially in schools without much classroom music time. According to the program’s manifesto, “Music Messenger was created in the belief that music is a universal language that has the ability to transcend the boundaries of culture, language, age, race, and socio-economic background. Music Messenger also holds the conviction that music has the ability to embrace these human differences as well as express the humanity that connects all of us. Music Messenger offers its programs as a means of using music as a language through which to speak and express one’s self.”

“With these kids, I dissect the music,” Koh explains. “In a fugato from Bach, I separate one line from the others. I get them to listen to the colorations that are possible with the violin, pizzicato versus a bowed stroke, double stops versus a single note, and how different dynamics change the meaning of a phrase. We start to uncover these different layers of meaning in music.

“I’ve always believed that music is multilayered. The first time you listen to a piece, you absorb only one level of it. It’s like seeing a photograph in black and white. Perhaps the second time you listen to it you start to see color, and the third or fourth time you begin to see dimensions, and finally it becomes a three-dimensional, colorful sculpture.

“With Music Messenger, I can show the kids how many layers there are, and then maybe on their own they can start seeing those beautiful sculptures in music.”

What Jennifer Koh Plays

For the past ten years, Jennifer Koh has applied a Tourte bow to the 1727 Ex-Grumiaux Ex-General DuPont Stradivari, both on loan from a private sponsor. “The moment I played on this particular violin it was like I met my soul mate,” she says. “Arthur Grumiaux has passed on, and so have a lot of people who were present when he was playing this instrument, but the person who performed on this instrument stays in the instrument. You feel that connection with Grumiaux, and between Grumiaux and his audiences, when you play an instrument with this kind of history. It definitely has changed me as a player. With a great instrument, just like in a relationship, you can’t just impose yourself on it. The more you get to know the instrument and its different timbres and colors, you become very connected to it. Now it’s an extension of myself, and it’s become hard to imagine myself playing on anything else.”

© Jennifer Koh, All Rights Reserved. Photography by Juergen Frank. Site by ycArt design studio